Which of the following English phonemes has more than one allophone based on its position in a word?

“The age of melancholy"is how psychologist Daniel Goleman describes our age.People today experience more depression than previousgenerations, despite the technological wonders that help us every day. It might be because of them.

Our lifestyles are increasingly driven by technology. Phones, computers and the Internet pervadeour days.There is a constant, nagging need to check for texts and emails. to update Facebook, MySpace and Linkedln profiles, to acquire the latestnotebook or cellphone.

Are we being served by these technological wonders or have we become enslaved by them? l studythe psychology of technology, and it seems to me that we are sleepwalking into a world where technology is severely affecting our well-being. Technology can be hugely useful in the fast lane of modern living, but we need to stop it from taking over.

For many of us, it is becoming increasingly difficult to control the impulse to check our inbox yet again or see whether the neailres arv in a similarsince we last looked. Our children are in a similar date on Facebook.In many homes, the computerhas become the centre of attention; it is the meanum through which we work and play.

How did this arise, and what is it doing to us? In this era of mass consumption, we are surrounded

by advertising that urges us to find a fultillment through the acquisition of material goods.As a result, adults and children increasingly believe that in order to belong and feel good about themselves, they must own the lasted model or gadget.Yet research by psychologist Tim Kasser of Knox college in Galesburg,linoIs,nas tnral aoals areple who place a high value on material goals are unhappier than those who are less materialistic.Materialism is also associated with lower self-esteem, greater narcissism, greater tendency to compare oneself unfavorably with other people, less empathy and more conflict in relationships.

our culture also constantly reminds us that time is money.This implies a need for total efficiency,which is why we are allowing laptop computers and mobile phones to blur the separation betweenwork and home.As one unhappy human-resource manager in a high-tech company put it: "Theygave me a mobile phone so they can own me 24hours a day, and a portable computer, so my office is now with me all the time—l cannot break outof this pressure.""Sound familiar?

Psychologists generally believe that the lack of aclear separation between work and home significantly damages our relationships with loved ones.lt also predispose us to focus on the here and now at the expense of long-term goals.

By imposing these twin pressures, modern society is in danger of swapping standard of living for quality of life. We need ways to help recover thoseincreasingly large parts of our lives that we haveceded to technology, to regain mastery over technology and learn to use it in a healthy and positive way.

What does Daniel Goleman attempt to ilustrate by calling the era "the age of melancholy”in Paragraph 1?

“The age of melancholy"is how psychologist Daniel Goleman describes our age.People today experience more depression than previousgenerations, despite the technological wonders that help us every day. It might be because of them.

Our lifestyles are increasingly driven by technology. Phones, computers and the Internet pervadeour days.There is a constant, nagging need to check for texts and emails. to update Facebook, MySpace and Linkedln profiles, to acquire the latestnotebook or cellphone.

Are we being served by these technological wonders or have we become enslaved by them? l studythe psychology of technology, and it seems to me that we are sleepwalking into a world where technology is severely affecting our well-being. Technology can be hugely useful in the fast lane of modern living, but we need to stop it from taking over.

For many of us, it is becoming increasingly difficult to control the impulse to check our inbox yet again or see whether the neailres arv in a similarsince we last looked. Our children are in a similar date on Facebook.In many homes, the computerhas become the centre of attention; it is the meanum through which we work and play.

How did this arise, and what is it doing to us? In this era of mass consumption, we are surrounded

by advertising that urges us to find a fultillment through the acquisition of material goods.As a result, adults and children increasingly believe that in order to belong and feel good about themselves, they must own the lasted model or gadget.Yet research by psychologist Tim Kasser of Knox college in Galesburg,linoIs,nas tnral aoals areple who place a high value on material goals are unhappier than those who are less materialistic.Materialism is also associated with lower self-esteem, greater narcissism, greater tendency to compare oneself unfavorably with other people, less empathy and more conflict in relationships.

our culture also constantly reminds us that time is money.This implies a need for total efficiency,which is why we are allowing laptop computers and mobile phones to blur the separation betweenwork and home.As one unhappy human-resource manager in a high-tech company put it: "Theygave me a mobile phone so they can own me 24hours a day, and a portable computer, so my office is now with me all the time—l cannot break outof this pressure.""Sound familiar?

Psychologists generally believe that the lack of aclear separation between work and home significantly damages our relationships with loved ones.lt also predispose us to focus on the here and now at the expense of long-term goals.

By imposing these twin pressures, modern society is in danger of swapping standard of living for quality of life. We need ways to help recover thoseincreasingly large parts of our lives that we haveceded to technology, to regain mastery over technology and learn to use it in a healthy and positive way.

What impact has been produced by technology on people according to Paragraph 2?

“The age of melancholy"is how psychologist Daniel Goleman describes our age.People today experience more depression than previousgenerations, despite the technological wonders that help us every day. It might be because of them.

Our lifestyles are increasingly driven by technology. Phones, computers and the Internet pervadeour days.There is a constant, nagging need to check for texts and emails. to update Facebook, MySpace and Linkedln profiles, to acquire the latestnotebook or cellphone.

Are we being served by these technological wonders or have we become enslaved by them? l studythe psychology of technology, and it seems to me that we are sleepwalking into a world where technology is severely affecting our well-being. Technology can be hugely useful in the fast lane of modern living, but we need to stop it from taking over.

For many of us, it is becoming increasingly difficult to control the impulse to check our inbox yet again or see whether the neailres arv in a similarsince we last looked. Our children are in a similar date on Facebook.In many homes, the computerhas become the centre of attention; it is the meanum through which we work and play.

How did this arise, and what is it doing to us? In this era of mass consumption, we are surrounded

by advertising that urges us to find a fultillment through the acquisition of material goods.As a result, adults and children increasingly believe that in order to belong and feel good about themselves, they must own the lasted model or gadget.Yet research by psychologist Tim Kasser of Knox college in Galesburg,linoIs,nas tnral aoals areple who place a high value on material goals are unhappier than those who are less materialistic.Materialism is also associated with lower self-esteem, greater narcissism, greater tendency to compare oneself unfavorably with other people, less empathy and more conflict in relationships.

our culture also constantly reminds us that time is money.This implies a need for total efficiency,which is why we are allowing laptop computers and mobile phones to blur the separation betweenwork and home.As one unhappy human-resource manager in a high-tech company put it: "Theygave me a mobile phone so they can own me 24hours a day, and a portable computer, so my office is now with me all the time—l cannot break outof this pressure.""Sound familiar?

Psychologists generally believe that the lack of aclear separation between work and home significantly damages our relationships with loved ones.lt also predispose us to focus on the here and now at the expense of long-term goals.

By imposing these twin pressures, modern society is in danger of swapping standard of living for quality of life. We need ways to help recover thoseincreasingly large parts of our lives that we haveceded to technology, to regain mastery over technology and learn to use it in a healthy and positive way.

What is the author most worried about concerning the change induced by technology?

“The age of melancholy"is how psychologist Daniel Goleman describes our age.People today experience more depression than previousgenerations, despite the technological wonders that help us every day. It might be because of them.

Our lifestyles are increasingly driven by technology. Phones, computers and the Internet pervadeour days.There is a constant, nagging need to check for texts and emails. to update Facebook, MySpace and Linkedln profiles, to acquire the latestnotebook or cellphone.

Are we being served by these technological wonders or have we become enslaved by them? l studythe psychology of technology, and it seems to me that we are sleepwalking into a world where technology is severely affecting our well-being. Technology can be hugely useful in the fast lane of modern living, but we need to stop it from taking over.

For many of us, it is becoming increasingly difficult to control the impulse to check our inbox yet again or see whether the neailres arv in a similarsince we last looked. Our children are in a similar date on Facebook.In many homes, the computerhas become the centre of attention; it is the meanum through which we work and play.

How did this arise, and what is it doing to us? In this era of mass consumption, we are surrounded

by advertising that urges us to find a fultillment through the acquisition of material goods.As a result, adults and children increasingly believe that in order to belong and feel good about themselves, they must own the lasted model or gadget.Yet research by psychologist Tim Kasser of Knox college in Galesburg,linoIs,nas tnral aoals areple who place a high value on material goals are unhappier than those who are less materialistic.Materialism is also associated with lower self-esteem, greater narcissism, greater tendency to compare oneself unfavorably with other people, less empathy and more conflict in relationships.

our culture also constantly reminds us that time is money.This implies a need for total efficiency,which is why we are allowing laptop computers and mobile phones to blur the separation betweenwork and home.As one unhappy human-resource manager in a high-tech company put it: "Theygave me a mobile phone so they can own me 24hours a day, and a portable computer, so my office is now with me all the time—l cannot break outof this pressure.""Sound familiar?

Psychologists generally believe that the lack of aclear separation between work and home significantly damages our relationships with loved ones.lt also predispose us to focus on the here and now at the expense of long-term goals.

By imposing these twin pressures, modern society is in danger of swapping standard of living for quality of life. We need ways to help recover thoseincreasingly large parts of our lives that we haveceded to technology, to regain mastery over technology and learn to use it in a healthy and positive way.

According to Tim Kasser, why are people obsessed with material pursuit?

“The age of melancholy"is how psychologist Daniel Goleman describes our age.People today experience more depression than previousgenerations, despite the technological wonders that help us every day. It might be because of them.

Our lifestyles are increasingly driven by technology. Phones, computers and the Internet pervadeour days.There is a constant, nagging need to check for texts and emails. to update Facebook, MySpace and Linkedln profiles, to acquire the latestnotebook or cellphone.

Are we being served by these technological wonders or have we become enslaved by them? l studythe psychology of technology, and it seems to me that we are sleepwalking into a world where technology is severely affecting our well-being. Technology can be hugely useful in the fast lane of modern living, but we need to stop it from taking over.

For many of us, it is becoming increasingly difficult to control the impulse to check our inbox yet again or see whether the neailres arv in a similarsince we last looked. Our children are in a similar date on Facebook.In many homes, the computerhas become the centre of attention; it is the meanum through which we work and play.

How did this arise, and what is it doing to us? In this era of mass consumption, we are surrounded

by advertising that urges us to find a fultillment through the acquisition of material goods.As a result, adults and children increasingly believe that in order to belong and feel good about themselves, they must own the lasted model or gadget.Yet research by psychologist Tim Kasser of Knox college in Galesburg,linoIs,nas tnral aoals areple who place a high value on material goals are unhappier than those who are less materialistic.Materialism is also associated with lower self-esteem, greater narcissism, greater tendency to compare oneself unfavorably with other people, less empathy and more conflict in relationships.

our culture also constantly reminds us that time is money.This implies a need for total efficiency,which is why we are allowing laptop computers and mobile phones to blur the separation betweenwork and home.As one unhappy human-resource manager in a high-tech company put it: "Theygave me a mobile phone so they can own me 24hours a day, and a portable computer, so my office is now with me all the time—l cannot break outof this pressure.""Sound familiar?

Psychologists generally believe that the lack of aclear separation between work and home significantly damages our relationships with loved ones.lt also predispose us to focus on the here and now at the expense of long-term goals.

By imposing these twin pressures, modern society is in danger of swapping standard of living for quality of life. We need ways to help recover thoseincreasingly large parts of our lives that we haveceded to technology, to regain mastery over technology and learn to use it in a healthy and positive way.

Which of the following would be the best title for the passage?

Speaking two languages rather than just。one has obvious practical benefits in an increasingly globalized world. But in recent years, scientists have begun to show that the advantages of biling ualism are even more fundamental than being able to converse with a wider range of people. Being bilingual, it turns out, makes you smarter. It can have a profound effect on your brain, improving cognitive skills not related to language and even shielding against dementia in old age.This view of bilingualism is remarkably different from the understanding of bilingualism through much of the 20th century. Researchers, educators and policy makers long considered a second language to be an interference, cognitively speaking, that hindered a child' s academic and intellectualdevelopment.

They were not wrong about the interference: there is ample evidence that in a bilingual' s brain both language systems are active even when he is using only one language, thus creating situations in which one system obstructs the other. But this interference, researchers are finding out, isn' t so much a handicap as a blessing in disguise. It forces the brain to resolve internal conflict, giving the mind a workout that strengthens its cognitive muscles Bilinguals, for instance, seem to be more adept than monolinguals at solving certain kinds of mental puzzles. In a 2004 study by the psychologists EIlen Bialystok and Michelle Martin- Rhee, bilingual and monolingual preschoolers were asked to sort blue circles and red squares presented on a computer screen into two digital bins- one marked with a blue square and the other marked with a red circle.

In the first task, the children had to sort the shapes by color, placing blue circles in the in marked with the blue square and red squares in the bin marked with the red circle. Both groups did this with comparable ease. Next, the children were asked to sort by shape, which was more challenging because it required placing the images in a bin marked with a conflicting color. The bilinguals were quicker at performing this task.The collective evidence from a number of such studies suggests that the bilingual experience improves the brain' s so-called executive function一 -acommand system that directs the attention processes that we use for planning, solving problems and performing various other mentally demanding tasks. These processes include ignoring distractions to stay focused, switching attention willfully from one thing to another and holding informationin mind一-like remembering a sequence of directions while driving.

Why does the tussle between two simultaneously active language systems improve these aspects 0f cognition? Until recently, researchers thought the bilingual advantage stemmed primarily from an ability for inhibition that was honed by the exercise of suppressing one language system: this suppression, it was thought, would help train the bilingual mind to ignore distractions in other contexts. But that explanation increasingly appears to be inadequate, since studies have shown that bilinguals perform better than monolinguals even at tasks that do not require inhibition, like threading a |ine through an ascending series of numbers scattered randomly on a page.

The key difference between bilinguals and monolinguals may be more basic: a heightened ability to monitor the environment. "Bilinguals have to switch languages quite often一you may talk to your father in one language and to your mother in another language," says Albert Costa, a researcher at the University of Pompeu Fabra in Spain. "It requires keeping track of changes around you in the same way that we monitor our surroundings when driving." In a study comparing German-ltalian bilinguals with Italian monolinguals on monitoring tasks, Mr. Costa and his collagues found that the bilingual subjects not only performed better,but they also did so with less activity in parts of the brain involved in monitoring, indicating that they were more efficient at it.

What can be inferred from the passage about the traditional view of bilingualism?

Speaking two languages rather than just。one has obvious practical benefits in an increasingly globalized world. But in recent years, scientists have begun to show that the advantages of biling ualism are even more fundamental than being able to converse with a wider range of people. Being bilingual, it turns out, makes you smarter. It can have a profound effect on your brain, improving cognitive skills not related to language and even shielding against dementia in old age.This view of bilingualism is remarkably different from the understanding of bilingualism through much of the 20th century. Researchers, educators and policy makers long considered a second language to be an interference, cognitively speaking, that hindered a child' s academic and intellectualdevelopment.

They were not wrong about the interference: there is ample evidence that in a bilingual' s brain both language systems are active even when he is using only one language, thus creating situations in which one system obstructs the other. But this interference, researchers are finding out, isn' t so much a handicap as a blessing in disguise. It forces the brain to resolve internal conflict, giving the mind a workout that strengthens its cognitive muscles Bilinguals, for instance, seem to be more adept than monolinguals at solving certain kinds of mental puzzles. In a 2004 study by the psychologists EIlen Bialystok and Michelle Martin- Rhee, bilingual and monolingual preschoolers were asked to sort blue circles and red squares presented on a computer screen into two digital bins- one marked with a blue square and the other marked with a red circle.

In the first task, the children had to sort the shapes by color, placing blue circles in the in marked with the blue square and red squares in the bin marked with the red circle. Both groups did this with comparable ease. Next, the children were asked to sort by shape, which was more challenging because it required placing the images in a bin marked with a conflicting color. The bilinguals were quicker at performing this task.The collective evidence from a number of such studies suggests that the bilingual experience improves the brain' s so-called executive function一 -acommand system that directs the attention processes that we use for planning, solving problems and performing various other mentally demanding tasks. These processes include ignoring distractions to stay focused, switching attention willfully from one thing to another and holding informationin mind一-like remembering a sequence of directions while driving.

Why does the tussle between two simultaneously active language systems improve these aspects 0f cognition? Until recently, researchers thought the bilingual advantage stemmed primarily from an ability for inhibition that was honed by the exercise of suppressing one language system: this suppression, it was thought, would help train the bilingual mind to ignore distractions in other contexts. But that explanation increasingly appears to be inadequate, since studies have shown that bilinguals perform better than monolinguals even at tasks that do not require inhibition, like threading a |ine through an ascending series of numbers scattered randomly on a page.

The key difference between bilinguals and monolinguals may be more basic: a heightened ability to monitor the environment. "Bilinguals have to switch languages quite often一you may talk to your father in one language and to your mother in another language," says Albert Costa, a researcher at the University of Pompeu Fabra in Spain. "It requires keeping track of changes around you in the same way that we monitor our surroundings when driving." In a study comparing German-ltalian bilinguals with Italian monolinguals on monitoring tasks, Mr. Costa and his collagues found that the bilingual subjects not only performed better,but they also did so with less activity in parts of the brain involved in monitoring, indicating that they were more efficient at it.

According to Bialystok and Martin-Rhee, why is the second task more challenging than the first one?

Speaking two languages rather than just。one has obvious practical benefits in an increasingly globalized world. But in recent years, scientists have begun to show that the advantages of biling ualism are even more fundamental than being able to converse with a wider range of people. Being bilingual, it turns out, makes you smarter. It can have a profound effect on your brain, improving cognitive skills not related to language and even shielding against dementia in old age.This view of bilingualism is remarkably different from the understanding of bilingualism through much of the 20th century. Researchers, educators and policy makers long considered a second language to be an interference, cognitively speaking, that hindered a child' s academic and intellectualdevelopment.

They were not wrong about the interference: there is ample evidence that in a bilingual' s brain both language systems are active even when he is using only one language, thus creating situations in which one system obstructs the other. But this interference, researchers are finding out, isn' t so much a handicap as a blessing in disguise. It forces the brain to resolve internal conflict, giving the mind a workout that strengthens its cognitive muscles Bilinguals, for instance, seem to be more adept than monolinguals at solving certain kinds of mental puzzles. In a 2004 study by the psychologists EIlen Bialystok and Michelle Martin- Rhee, bilingual and monolingual preschoolers were asked to sort blue circles and red squares presented on a computer screen into two digital bins- one marked with a blue square and the other marked with a red circle.

In the first task, the children had to sort the shapes by color, placing blue circles in the in marked with the blue square and red squares in the bin marked with the red circle. Both groups did this with comparable ease. Next, the children were asked to sort by shape, which was more challenging because it required placing the images in a bin marked with a conflicting color. The bilinguals were quicker at performing this task.The collective evidence from a number of such studies suggests that the bilingual experience improves the brain' s so-called executive function一 -acommand system that directs the attention processes that we use for planning, solving problems and performing various other mentally demanding tasks. These processes include ignoring distractions to stay focused, switching attention willfully from one thing to another and holding informationin mind一-like remembering a sequence of directions while driving.

Why does the tussle between two simultaneously active language systems improve these aspects 0f cognition? Until recently, researchers thought the bilingual advantage stemmed primarily from an ability for inhibition that was honed by the exercise of suppressing one language system: this suppression, it was thought, would help train the bilingual mind to ignore distractions in other contexts. But that explanation increasingly appears to be inadequate, since studies have shown that bilinguals perform better than monolinguals even at tasks that do not require inhibition, like threading a |ine through an ascending series of numbers scattered randomly on a page.

The key difference between bilinguals and monolinguals may be more basic: a heightened ability to monitor the environment. "Bilinguals have to switch languages quite often一you may talk to your father in one language and to your mother in another language," says Albert Costa, a researcher at the University of Pompeu Fabra in Spain. "It requires keeping track of changes around you in the same way that we monitor our surroundings when driving." In a study comparing German-ltalian bilinguals with Italian monolinguals on monitoring tasks, Mr. Costa and his collagues found that the bilingual subjects not only performed better,but they also did so with less activity in parts of the brain involved in monitoring, indicating that they were more efficient at it.

How is language interference perceived by modern researchers according to the passage?

Speaking two languages rather than just。one has obvious practical benefits in an increasingly globalized world. But in recent years, scientists have begun to show that the advantages of biling ualism are even more fundamental than being able to converse with a wider range of people. Being bilingual, it turns out, makes you smarter. It can have a profound effect on your brain, improving cognitive skills not related to language and even shielding against dementia in old age.This view of bilingualism is remarkably different from the understanding of bilingualism through much of the 20th century. Researchers, educators and policy makers long considered a second language to be an interference, cognitively speaking, that hindered a child' s academic and intellectualdevelopment.

They were not wrong about the interference: there is ample evidence that in a bilingual' s brain both language systems are active even when he is using only one language, thus creating situations in which one system obstructs the other. But this interference, researchers are finding out, isn' t so much a handicap as a blessing in disguise. It forces the brain to resolve internal conflict, giving the mind a workout that strengthens its cognitive muscles Bilinguals, for instance, seem to be more adept than monolinguals at solving certain kinds of mental puzzles. In a 2004 study by the psychologists EIlen Bialystok and Michelle Martin- Rhee, bilingual and monolingual preschoolers were asked to sort blue circles and red squares presented on a computer screen into two digital bins- one marked with a blue square and the other marked with a red circle.

In the first task, the children had to sort the shapes by color, placing blue circles in the in marked with the blue square and red squares in the bin marked with the red circle. Both groups did this with comparable ease. Next, the children were asked to sort by shape, which was more challenging because it required placing the images in a bin marked with a conflicting color. The bilinguals were quicker at performing this task.The collective evidence from a number of such studies suggests that the bilingual experience improves the brain' s so-called executive function一 -acommand system that directs the attention processes that we use for planning, solving problems and performing various other mentally demanding tasks. These processes include ignoring distractions to stay focused, switching attention willfully from one thing to another and holding informationin mind一-like remembering a sequence of directions while driving.

Why does the tussle between two simultaneously active language systems improve these aspects 0f cognition? Until recently, researchers thought the bilingual advantage stemmed primarily from an ability for inhibition that was honed by the exercise of suppressing one language system: this suppression, it was thought, would help train the bilingual mind to ignore distractions in other contexts. But that explanation increasingly appears to be inadequate, since studies have shown that bilinguals perform better than monolinguals even at tasks that do not require inhibition, like threading a |ine through an ascending series of numbers scattered randomly on a page.

The key difference between bilinguals and monolinguals may be more basic: a heightened ability to monitor the environment. "Bilinguals have to switch languages quite often一you may talk to your father in one language and to your mother in another language," says Albert Costa, a researcher at the University of Pompeu Fabra in Spain. "It requires keeping track of changes around you in the same way that we monitor our surroundings when driving." In a study comparing German-ltalian bilinguals with Italian monolinguals on monitoring tasks, Mr. Costa and his collagues found that the bilingual subjects not only performed better,but they also did so with less activity in parts of the brain involved in monitoring, indicating that they were more efficient at it.

Which of the following is closest in meaning to the underlined word "tussle"in Paragrah7?

Speaking two languages rather than just。one has obvious practical benefits in an increasingly globalized world. But in recent years, scientists have begun to show that the advantages of biling ualism are even more fundamental than being able to converse with a wider range of people. Being bilingual, it turns out, makes you smarter. It can have a profound effect on your brain, improving cognitive skills not related to language and even shielding against dementia in old age.This view of bilingualism is remarkably different from the understanding of bilingualism through much of the 20th century. Researchers, educators and policy makers long considered a second language to be an interference, cognitively speaking, that hindered a child' s academic and intellectualdevelopment.

They were not wrong about the interference: there is ample evidence that in a bilingual' s brain both language systems are active even when he is using only one language, thus creating situations in which one system obstructs the other. But this interference, researchers are finding out, isn' t so much a handicap as a blessing in disguise. It forces the brain to resolve internal conflict, giving the mind a workout that strengthens its cognitive muscles Bilinguals, for instance, seem to be more adept than monolinguals at solving certain kinds of mental puzzles. In a 2004 study by the psychologists EIlen Bialystok and Michelle Martin- Rhee, bilingual and monolingual preschoolers were asked to sort blue circles and red squares presented on a computer screen into two digital bins- one marked with a blue square and the other marked with a red circle.

In the first task, the children had to sort the shapes by color, placing blue circles in the in marked with the blue square and red squares in the bin marked with the red circle. Both groups did this with comparable ease. Next, the children were asked to sort by shape, which was more challenging because it required placing the images in a bin marked with a conflicting color. The bilinguals were quicker at performing this task.The collective evidence from a number of such studies suggests that the bilingual experience improves the brain' s so-called executive function一 -acommand system that directs the attention processes that we use for planning, solving problems and performing various other mentally demanding tasks. These processes include ignoring distractions to stay focused, switching attention willfully from one thing to another and holding informationin mind一-like remembering a sequence of directions while driving.

Why does the tussle between two simultaneously active language systems improve these aspects 0f cognition? Until recently, researchers thought the bilingual advantage stemmed primarily from an ability for inhibition that was honed by the exercise of suppressing one language system: this suppression, it was thought, would help train the bilingual mind to ignore distractions in other contexts. But that explanation increasingly appears to be inadequate, since studies have shown that bilinguals perform better than monolinguals even at tasks that do not require inhibition, like threading a |ine through an ascending series of numbers scattered randomly on a page.

The key difference between bilinguals and monolinguals may be more basic: a heightened ability to monitor the environment. "Bilinguals have to switch languages quite often一you may talk to your father in one language and to your mother in another language," says Albert Costa, a researcher at the University of Pompeu Fabra in Spain. "It requires keeping track of changes around you in the same way that we monitor our surroundings when driving." In a study comparing German-ltalian bilinguals with Italian monolinguals on monitoring tasks, Mr. Costa and his collagues found that the bilingual subjects not only performed better,but they also did so with less activity in parts of the brain involved in monitoring, indicating that they were more efficient at it.

Which of the following would be the best title for the passage?

请列出四种英语阅读技能,并分别写出一句课堂教学指令语以培养相应的技能。

根据题意回答问题。

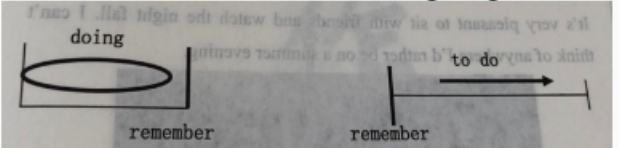

下面内容是某教师讲解remember doing something和remember to do something语言点时的课堂实录。 Teacher: Li Hua, what did you do last Sunday morning? Li Hua: I played badminton with my friends. Teacher (to the class): Did Hua remember playingbadminton with her friends? Students: Yes, she did Teacher: Liu Ying, what did you do last Sunday morning? Liu Ying: I visited my grandparents Teacher (to the class): Did Liu Ying remember visi ting her grandparents? Students: Yes, she did. Teacher: What will you do this Sunday morning then, Liu Ying? Liu Ying: I will see a film with my sister Teacher: Please remember to take the tickets with you and be there on time. Liu Ying: Sure, I will remember to do that. Thank you. Teacher: Now, class. Can you tell the difference between "remember doing sth." and "remember to do sth." ? Look at the following diagrams:

请根据此教学情景回答下列问题:

该教师在讲解知识点时运用了哪两种方法?

这些方法各自有何特点?能发挥什么作用?

使用这些方法时应重点注意什么?

根据提供的信息和语素材设计教学方案,用英文作答设计任务:根据下列学生信息和语言素材,设计20分钟英语读写课的教学方案。教案没有固定格式,但须包含下列要点: (1) teaching objectives (2) teaching contents (3) key and difficult points (4) major steps and time allocation (5) activities and justifications 教学时间: 20分钟 学生概况:某城镇普通高中一年级学生,班级人数40人;多数学生的英语水平达到了课标的相应要求,课堂参与积极性一般。 语言素材: In the summer when | want to relax, | go down to the river at the edge of our village.There is a deep pond there and all the village children meet in hot weather to swim The tall trees along the river bank give us shade when we just want to sit and talk and the sandy river bank is perfect for the little children to play on. On the opposite river bank are some large rocks to which we older children swim when we want to sunbathe. The river flows slowly and water is crysta I clear. The air smells of trees and damp earth and my worries begin to disappear as soon asI arrive Sometimes on warm evenings we take food and drink down to the river. It’s very pleasant to sit with friends and watch the night fall.I can' t think of anywhere I' d rather be on a summer evening.

根据题意回答问题。